Myoglobin and hemoglobin differ mainly in their location, function, oxygen affinity, and structure. Myoglobin stores oxygen in muscles for immediate use, while hemoglobin transports oxygen through blood. Myoglobin has one heme group, hemoglobin has four. Myoglobin binds oxygen tightly; hemoglobin releases it easily.

Before diving into differences, let's define each protein simply. Think of them as two specialized workers in the body's oxygen economy, each with a unique job description and workplace.

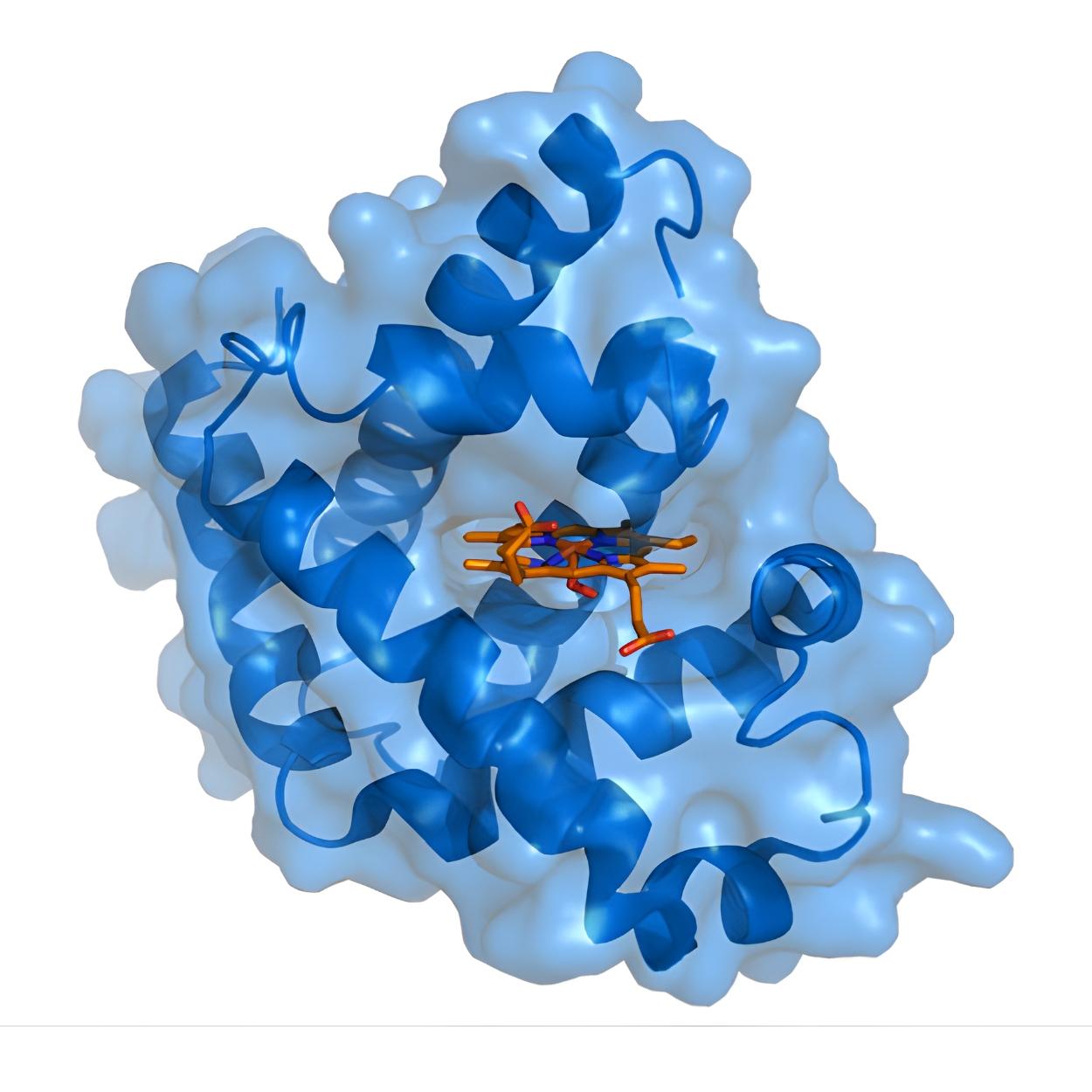

Myoglobin is the oxygen reservoir of your muscles. Found abundantly in skeletal and cardiac muscle tissue, its sole job is to store oxygen. Structurally, it's a single polypeptide chain wrapped around one heme group (an iron-containing compound). This simple structure is key to its function. Clinically, when muscle is damaged, myoglobin floods into the bloodstream, making it a sensitive marker for conditions like rhabdomyolysis or, historically, heart attacks.

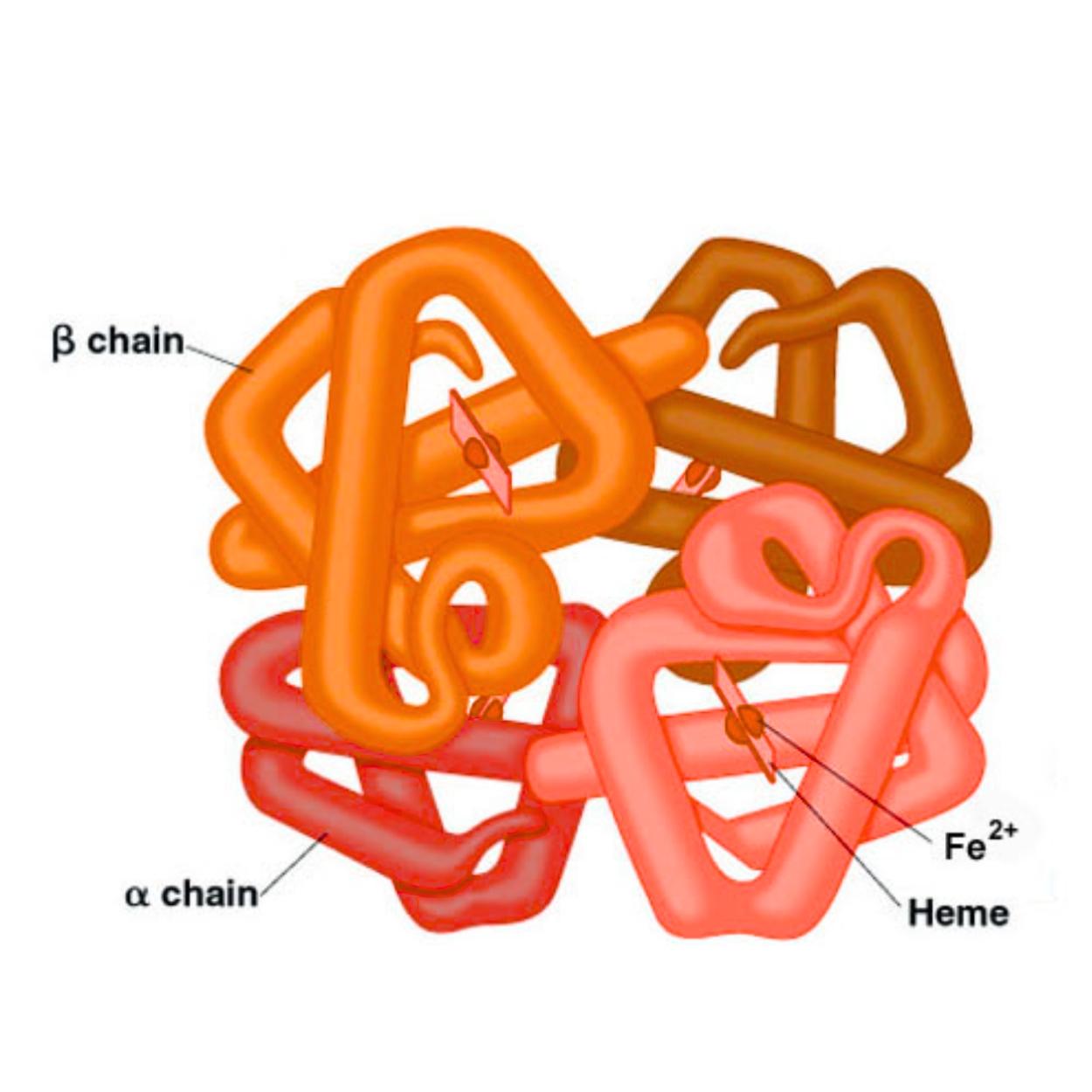

Hemoglobin is the oxygen transport system of your body. Residing inside red blood cells, it’s a molecular shuttle that picks up oxygen from the lungs and delivers it to tissues. Its structure is more complex: a tetramer composed of four polypeptide chains (typically two alpha and two beta), each with its own heme group. This quartet allows for sophisticated teamwork. Common variants include HbA (adult hemoglobin), HbF (fetal hemoglobin, with a higher oxygen affinity), and HbS (the abnormal form in sickle cell anemia).

This is a common point of confusion. The short answer is no, myoglobin is not blood. Blood is a complex tissue containing red blood cells (which carry hemoglobin), white cells, platelets, and plasma. Myoglobin is a protein inside muscle cells. The red color in meat is primarily from myoglobin, not blood, which is largely drained during processing. They are distinct proteins in different locations, united only by their iron-based, oxygen-loving chemistry.

Not all hemoglobin is identical. The body produces different types for specific needs:

|

Type |

Primary Role & Trait |

|

The dominant form in adults, with standard oxygen-carrying properties. |

|

|

A minor adult component; levels can rise in conditions like beta-thalassemia. |

|

|

Has a higher oxygen affinity than HbA, allowing a fetus to efficiently extract oxygen from maternal blood. |

|

|

A genetic variant where a single amino acid change causes red cells to sickle under stress, leading to sickle cell disease. |

The switch from HbF to HbA after birth is a crucial developmental milestone. Monitoring hemoglobin types is vital in diagnosing hemoglobinopathies and understanding conditions like pregnancy, where physiological changes occur.

The core distinction lies in their design philosophy: one for storage, one for transport. The following table summarizes the basic difference of myoglobin and hemoglobin across key parameters:

|

Feature |

Myoglobin |

Hemoglobin |

|

Location |

Muscle cells (skeletal & cardiac) |

Red Blood Cells (Erythrocytes) |

|

Structure |

Single polypeptide chain (monomer) |

Four chains: Tetramer (α₂β₂) |

|

Oxygen Affinity |

Very High (Strong, tight binding) |

Lower (Releases oxygen readily) |

|

P50 Value |

Very Low (~1-2 mm Hg) |

Higher (~26 mm Hg) |

|

Oxygen Dissociation Curve |

Hyperbolic (Simple, steady binding) |

Sigmoidal (Cooperative, efficient release) |

|

Primary Function |

Oxygen Storage in muscle tissue |

Oxygen Transport from lungs to tissues |

|

Binding Sites |

1 heme group, 1 oxygen molecule |

4 heme groups, 4 oxygen molecules |

|

Clinical Importance |

Marker for muscle injury (Rhabdomyolysis) |

Indicator of blood disorders (Anemia, Polycythemia) |

The functional differences are written in their molecular architecture.

Myoglobin is a compact, globular protein made of about 153 amino acids in a single chain. At its heart lies one heme group, a porphyrin ring with a central iron atom (Fe²⁺) that binds the oxygen molecule. Its simple, rounded structure is ideal for holding onto oxygen tightly within the muscle cell environment.

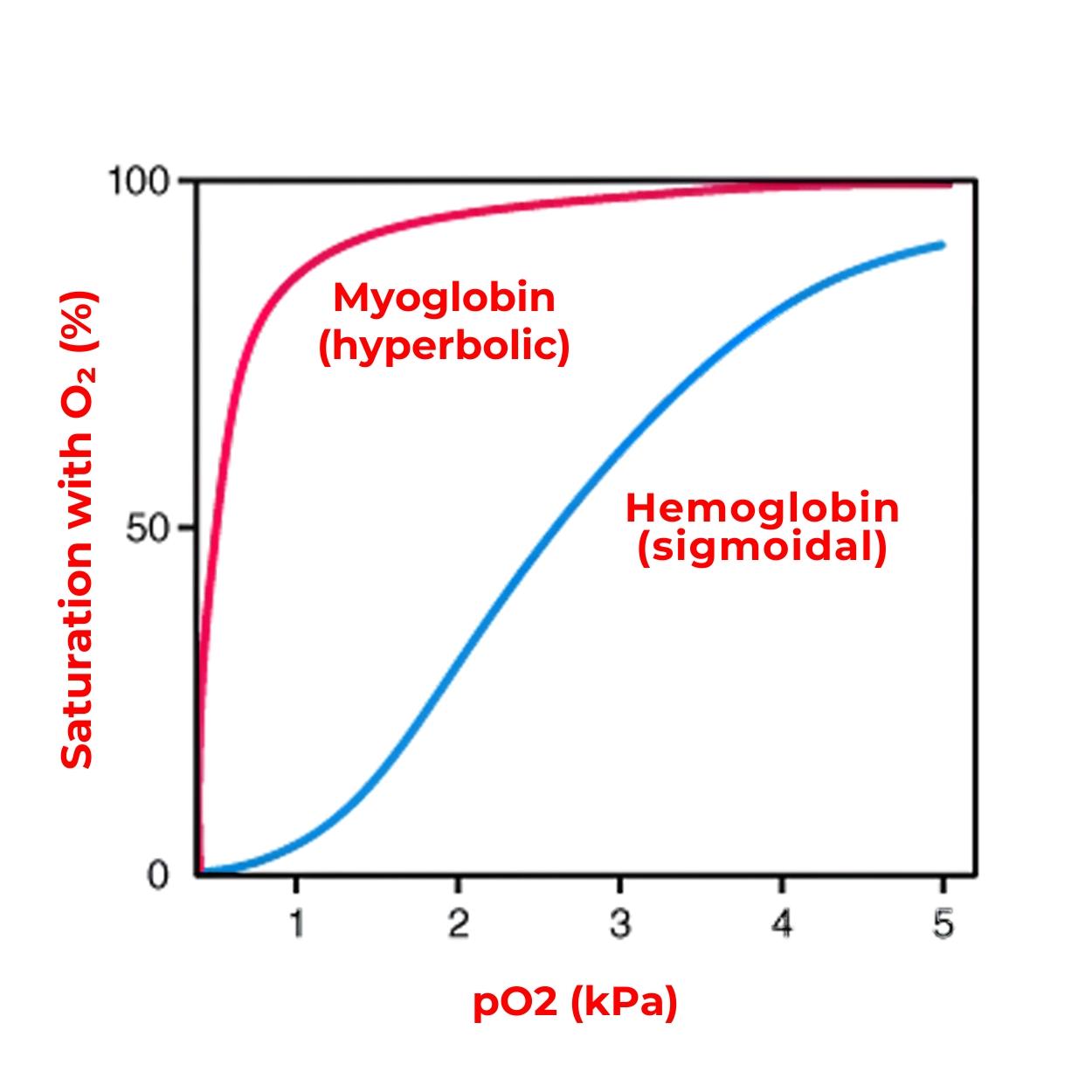

"Better" depends on the goal: holding or delivering. This is best seen in their oxygen dissociation curves.

Myoglobin's curve is hyperbolic. It binds oxygen tightly even at very low partial pressures (like those found in exercising muscle), with a low P50 (the pressure at which the protein is 50% saturated). This high affinity makes it an excellent oxygen reserve tank, only releasing oxygen when levels in the muscle cell become critically low.

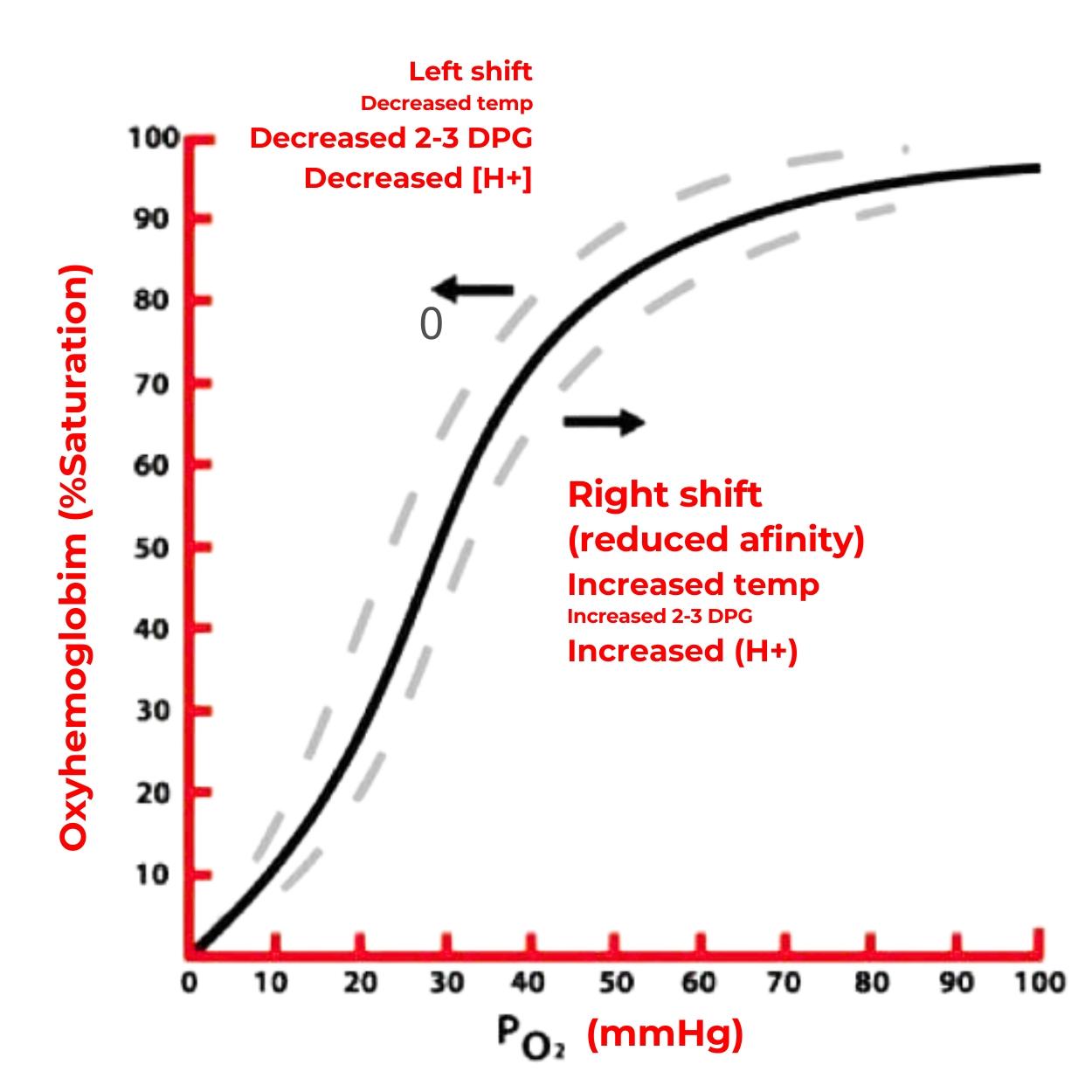

Hemoglobin's curve is distinctively sigmoidal (S-shaped), a direct result of cooperative binding. It loads oxygen efficiently in the high-pressure environment of the lungs and, crucially, releases it readily in the lower-pressure, acidic, CO₂-rich environment of the tissues. This phenomenon, where increased CO₂ and decreased pH promote oxygen release, is known as the Bohr Effect. This lower affinity (higher P50) is what makes hemoglobin a superb delivery system.

Imagine a city's water supply. You need both a central reservoir (hemoglobin in blood) and local water towers in every neighborhood (myoglobin in muscles) to ensure immediate, on-demand supply and prevent shortages during peak usage.

Hemoglobin is the delivery truck network, constantly moving oxygen from the lungs (the supplier) to all parts of the body. Myoglobin is the local storage tank within each muscle factory. Without hemoglobin, oxygen never reaches the muscles. Without myoglobin, muscles would have to rely solely on the passing blood supply, faltering during intense, sustained activity like running or swimming when oxygen demand outstrips immediate delivery.

During aerobic exercise, muscle cells consume oxygen rapidly. Myoglobin acts as a buffer, releasing its stored oxygen directly to the mitochondria to keep energy production running smoothly. This is especially critical in heart muscle, which must contract relentlessly without fatigue.

Hemoglobin's role is systemic. It binds oxygen in the lungs, forms oxyhemoglobin (bright red), travels via arteries, and releases oxygen in capillaries where tissue pressure is low. The now-deoxygenated hemoglobin (darker red) returns to the lungs via veins. It also aids in CO₂ transport and buffering blood pH.

The graphical representation of their oxygen binding myoglobin’s high-affinity hyperbolic curve sitting above hemoglobin’s sigmoidal curve visually encapsulates their relationship. Myoglobin’s curve ensures it pulls oxygen from hemoglobin in the capillaries, effectively "unloading" the delivery truck into the local storage.

Their presence in the bloodstream tells very different clinical stories.

Because myoglobin is normally confined to muscle, its detection in blood is a red flag for muscle injury. It is a rapid, early marker for rhabdomyolysis (severe muscle breakdown) from trauma, extreme exertion, or toxins. It was once used to diagnose heart attacks but has been largely replaced by more cardiac-specific troponins.

Hemoglobin levels are a cornerstone of blood tests. Low levels indicate anemia, while high levels suggest polycythemia. Abnormal forms, as in hemoglobinopathies (sickle cell anemia, thalassemia), cause severe disease. It is a primary indicator of the blood's oxygen-carrying capacity and overall health.

That red juice in your raw steak packaging? It's mostly water and myoglobin, not blood. The red color of meat correlates with myoglobin content beef is rich in it, chicken breast has less. Cooking denatures the protein, changing the iron's state and turning the meat from red to brown. A rare steak is red because its internal myoglobin is still oxygenated (bright red), not because it's "bloody" so, you can confidently enjoy your steak knowing its 'juices' are a sign of protein, not blood.

The appearance of myoglobin-rich liquid is normal. Regarding dietary laws that prohibit eating blood, it's important to note that properly slaughtered and drained meat contains minimal actual blood; the residual color is primarily myoglobin.

Myoglobinuria is the presence of myoglobin in urine, typically following massive muscle trauma (crush injury, statin toxicity). This can lead to acute kidney injury if the protein precipitates in renal tubules.

|

Aspect |

Myoglobin |

Hemoglobin |

|

Role |

Intracellular Oxygen Storage |

Oxygen Transport in Blood |

|

Site |

Muscle Tissue |

Red Blood Cells |

|

Molecular Shape |

Monomer |

Tetramer |

|

Oxygen Binding |

Tight (High Affinity) |

Cooperative (Releases Easily) |

|

Key Curve |

Hyperbolic |

Sigmoidal |

|

Clinical Marker |

Muscle Damage |

Blood Disorders & Oxygen Capacity |

Q1. Are blood and myoglobin the same thing?

Answer: No, they are not. Blood is a connective tissue containing cells and plasma. Myoglobin is a specific protein found within muscle cells. The red color in meat is primarily from myoglobin, not leftover blood.

Q2.What is hemoglobin’s main job?

Answer: Hemoglobin's main job is to transport oxygen from the lungs to all the tissues of the body and to help carry some carbon dioxide back from the tissues to the lungs for exhalation.

Q3.Which has higher oxygen affinity, myoglobin or hemoglobin?

Answer: Myoglobin has a significantly higher oxygen affinity than hemoglobin. It binds oxygen more tightly and holds onto it, while hemoglobin is designed to bind and release oxygen easily during its transport cycle.

Q4.Why does hemoglobin show a sigmoidal curve?

Answer: The sigmoidal (S-shaped) curve of hemoglobin is due to cooperative binding. When one oxygen molecule binds to a heme group, it induces a conformational change that makes it easier for the next heme groups to bind oxygen. This allows for efficient loading in the lungs and unloading in the tissues.

Q5.Why is myoglobin not good for oxygen transport?

Answer: Myoglobin is not good for transport precisely because its affinity is too high. It acts like a trap, holding oxygen tightly and not releasing it readily under the conditions present in circulating blood. Hemoglobin's lower, regulatable affinity is essential for controlled delivery.

Q6.How many heme groups are in hemoglobin?

Answer: There are four heme groups in a single hemoglobin molecule, one embedded within each of its four polypeptide subunits. Each heme can bind one oxygen molecule.

Q7.What is the clinical use of myoglobin levels?

Answer: Clinically, elevated blood myoglobin levels are used primarily as an early, sensitive marker for acute muscle injury, such as in rhabdomyolysis, severe trauma, or extreme overexertion.

Q8.Can hemoglobin levels change during pregnancy?

Answer: Yes, it is normal and expected for hemoglobin levels to change during pregnancy. Hemoglobin often decreases due to hemodilution (a greater increase in plasma volume than in red cell mass), leading to physiological anemia of pregnancy, which is closely monitored.

Q9.What is the role of fetal hemoglobin (HbF)?

Answer: Fetal hemoglobin (HbF) has a higher oxygen affinity than adult hemoglobin (HbA). This allows the developing fetus to efficiently "pull" oxygen from the mother's bloodstream across the placenta, ensuring adequate oxygen supply for growth and development.