Hemoglobin disorders refer to a collection of inherited blood conditions that directly impact how red blood cells function within the body. These essential cells are responsible for carrying oxygen from the respiratory system to tissues and organs throughout the body. When someone has a hemoglobin disorder, their red blood cells may be reduced in quantity, unable to transport oxygen effectively, or both.

Among the various types of hemoglobinopathies, sickle cell anemia and thalassemia syndromes stand out as the most frequently encountered in clinical practice. Interestingly, carrying certain genetic variations linked to these conditions offers a natural defense against malaria a serious infectious disease spread by mosquito bites. Over many generations, this protective advantage has led to higher frequencies of these gene variants in populations living in malaria endemic regions across the globe.

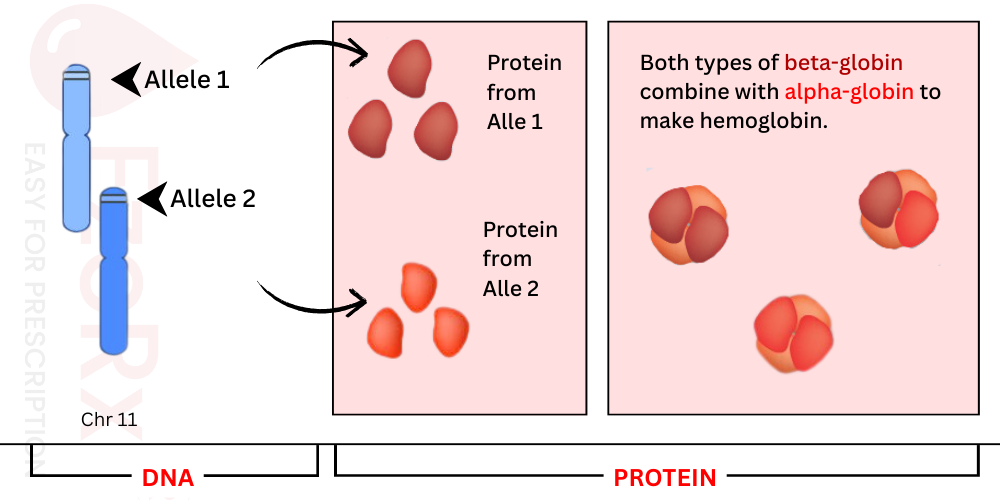

At the heart of hemoglobin production lies the HBB gene, located on chromosome 11. This gene carries the instructions for creating beta globin, a protein that pairs up with alpha globin to form the complete hemoglobin molecule. Think of it like a team where two beta globin and two alpha globin players join forces to make oxygen transport possible throughout the body.

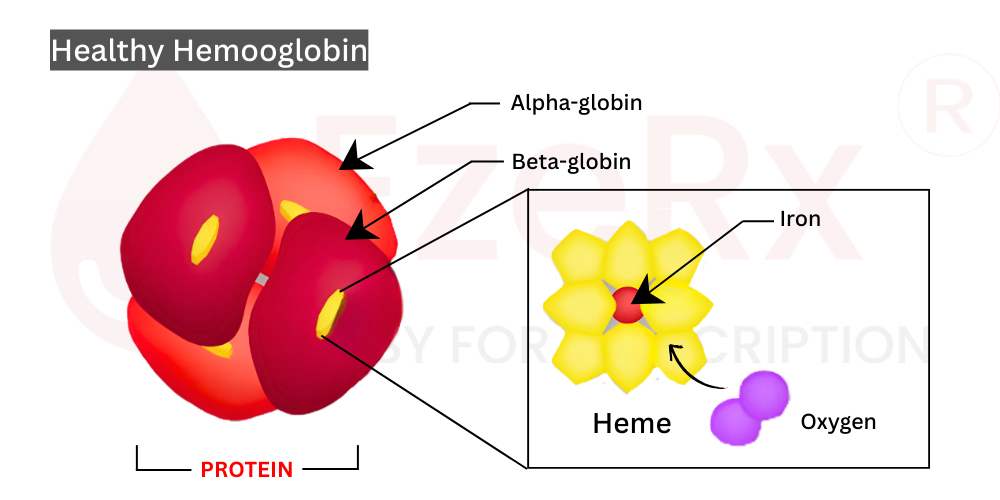

Hemoglobin isn't just any protein it's the principal component of red blood cells, giving blood its characteristic red hue and enabling its oxygen carrying superpower. That rich red color comes from heme groups, tiny iron containing structures nestled inside each globin protein. Without these heme molecules, hemoglobin simply can't grab onto oxygen and deliver it where it's needed.

Here's where things get interesting from a genetic standpoint. The HBB gene comes in multiple variants, technically called alleles. Each allele produces a slightly different version of beta globin. While most of these variations are harmless, some can trigger hereditary blood conditions. The clinical presentation varies widely depending on which specific allele a person inherits symptoms can be barely noticeable or profoundly life altering. But here's the common thread: in every case, the underlying problem traces back to dysfunctional hemoglobin that compromises red blood cell performance.

When clinicians look at beta globin problems, they typically sort them into two buckets:

Quantitative Deficiencies: Certain HBB gene alleles simply don't produce enough beta globin protein sometimes barely any at all. This scarcity leads to specific types of beta thalassemia, where patients end up with insufficient red blood cells circulating in their bloodstream. It's like a factory running at half capacity.

Qualitative Defects: Other alleles churn out beta globin that looks unusual or behaves abnormally. The consequences depend on exactly how the protein structure gets altered:

Each of these scenarios ultimately boils down to hemoglobin that can't perform its primary job effectively, whether due to quantity issues, structural problems, or functional impairments at the molecular level.

.png)

Every person carries two copies of the HBB gene one inherited from their mother and one from their father. These paired genes work together to determine what kind of hemoglobin gets produced in the body.

When it comes to how these genes actually function, the HBB alleles operate in a co-dominant fashion. What does that mean clinically? Simply put, both gene copies are actively producing beta globin proteins, and these proteins randomly mix together to assemble complete hemoglobin molecules. Neither allele silences the other both have a voice in the final product.

For most individuals carrying one healthy HBB allele alongside one problematic copy, the body manages just fine. That single functioning gene typically produces enough normal beta globin to keep red blood cells working properly. This explains why most hemoglobin disorders follow an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern a person needs to inherit two non working alleles (one from each parent) before the condition actually manifests.

Sickle cell disease and the majority of beta thalassemia syndromes fall into this category. Both parents may be carriers without showing symptoms themselves, but their child can inherit the full blown disorder if both pass along affected genes.

Here's where things deviate from the standard rule. Some hemoglobin disorders break the recessive mold and follow an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. In these cases, inheriting just one abnormal HBB allele is sufficient to cause disease. A parent with the disorder has a 50% chance of passing it directly to their child.

This pattern shows up in certain oxygen transport disorders and specific variants of beta thalassemia. The affected gene copy essentially overrides the healthy one, leading to clinical symptoms even with a single problematic allele.

The genetic picture gets even more nuanced when someone inherits two different types of abnormal alleles. Consider these scenarios:

In these compound heterozygous states, the clinical presentation reflects a co dominant pattern at the disease level. The symptoms don't come from just one allele or the other they represent the combined effects of both genetic variations working together. The result can be a unique clinical picture that differs from either condition alone.

This explains why two patients with "sickle cell disease" might have different experiences their second allele matters tremendously in shaping the overall disease expression.

The vast majority of beta globin production happens inside erythrocytes what we commonly call red blood cells. These specialized cells serve as the primary home for hemoglobin, containing about 98 99% of all beta globin found in the body. A few other tissues show low level hemoglobin expression, including pulmonary epithelial cells, retinal tissues, and the endometrial lining of the female reproductive tract. However, in these locations, hemoglobin doesn't play the same critical oxygen transport role it does in circulation.

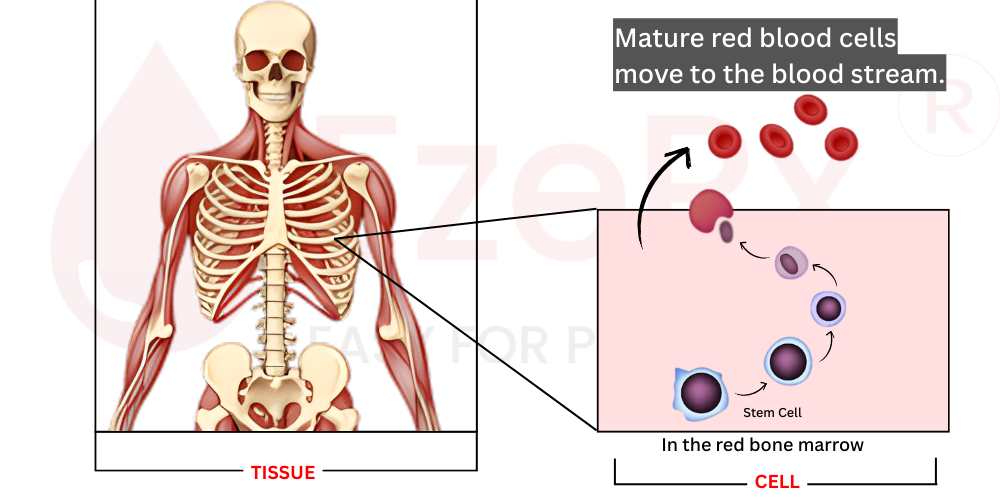

Red blood cell production, technically called erythropoiesis, takes place in the bone marrow specifically within the red marrow found in certain bones like the skull, sternum, ribs, and vertebrae. The process begins with hematopoietic stem cells, which serve as parent cells for all blood components.

As these precursor cells mature through various stages, something remarkable happens: the genes responsible for globin production get systematically activated. The developing cells gradually fill up with hemoglobin molecules. Eventually, once the cell is packed with enough hemoglobin, it ejects its nucleus a dramatic step that gives mature red blood cells their distinctive biconcave disc shape and flexibility. These newly formed erythrocytes then enter the peripheral circulation, ready to transport oxygen for months to come.

Once released into the bloodstream, each red blood cell has a finite lifespan of approximately 100 to 120 days (about 3 4 months). After this period, aging cells get removed from circulation and recycled by the spleen and liver, with their components including iron from heme being salvaged for new cell production.

The human body maintains precise control over this process. In a healthy adult, the bone marrow operates like a well oiled factory, producing an astonishing 2 to 3 million new red blood cells every single second. This constant renewal ensures adequate oxygen delivery to every tissue.

Here's a fascinating clinical observation about patients with beta globin disorders, they enter the world looking perfectly healthy. Not a hint of disease at birth. Why?

The answer lies in fetal hemoglobin, technically called HbF. During gestation, the developing baby produces this special type of hemoglobin that uses different globin chains specifically gamma globin instead of beta globin. Fetal hemoglobin actually has a higher oxygen affinity than adult hemoglobin, which helps extract oxygen from the maternal circulation across the placenta.

Around the time of birth, a carefully orchestrated hemoglobin switching process begins. The genes producing gamma globin gradually get silenced while beta globin production ramps up. Adult hemoglobin (HbA) slowly replaces fetal hemoglobin in circulating red blood cells.

This transition doesn't happen overnight. It takes several months for fetal hemoglobin to be substantially replaced by adult hemoglobin. That's why infants with severe beta globin disorders even conditions like major beta thalassemia or sickle cell disease typically don't show symptoms until 3 to 6 months of age. By then, enough fetal hemoglobin has been replaced by defective adult hemoglobin for the underlying disorder to become clinically apparent.

This developmental timeline has important implications for both early diagnosis and potential therapeutic strategies, including medications that can reactivate fetal hemoglobin production later in life.

Let's talk about just how essential red blood cells really are. These remarkable cells make up the largest cellular component of blood and actually represent the most abundant cell type circulating through the human body. Their mission? One primary job that literally keeps us alive, transporting oxygen from the lungs to every single tissue, organ, and cell that needs it.

Think about it your brain, your heart, your muscles during exercise, even the cells repairing a paper cut all depend on this steady oxygen supply. Without properly functioning red blood cells, the whole system starts breaking down.

So what makes red blood cells such effective oxygen carriers? The answer lies in hemoglobin, and at the core of hemoglobin sits beta globin protein. Beta globin doesn't work alone it partners with alpha globin to form the complete hemoglobin molecule. This partnership is absolutely essential. Think of them as dance partners; if one doesn't show up or moves wrong, the whole performance falls apart.

When beta globin is compromised whether through quantitative deficiencies (not enough protein) or qualitative defects (abnormal protein structure) the consequences ripple throughout the entire oxygen delivery system. Red blood cells can't do their job effectively, and blood tissue as a whole loses its ability to maintain proper oxygenation throughout the body.

The clinical presentation varies tremendously depending on the specific genetic mutation and which HBB gene variants a patient carries. But certain patterns emerge:

Anemia shows up in many forms patients may have frankly low red blood cell counts, or their cells might be present but dysfunctional. Either way, tissues end up starved for oxygen.

Pain episodes particularly characteristic of sickle cell disorders occur when misshapen red blood cells get stuck in small blood vessels, blocking flow and causing tissue ischemia.

Organ damage accumulates over time. When organs don't receive adequate oxygen, or when abnormal cells clog circulation, the heart, lungs, kidneys, spleen, and brain can all suffer chronic injury.

Systemic hypoxemia low oxygen levels throughout the body represents the most direct consequence. Without healthy hemoglobin, even perfectly functioning lungs can't get oxygen where it needs to go.

The specific combination of symptoms depends on the precise genotype phenotype correlation that is, how the underlying genetic change translates into clinical disease expression. Some patients experience mild laboratory abnormalities without significant symptoms, while others face life threatening complications from early childhood.

We'll dive deeper into specific disorders and their clinical presentations in the upcoming section.

One of the most striking aspects of hemoglobinopathies is just how differently they present from person to person. The clinical spectrum ranges from individuals who live their entire lives without noticing any symptoms to patients facing life threatening complications from early infancy. Symptom onset can happen at any point some babies show signs within months of birth, while others don't develop noticeable issues until adulthood.

What determines this variability? It comes down to the specific HBB gene mutations involved. Different alleles produce different clinical pictures. And when patients inherit compound heterozygous combinations two different abnormal alleles they may present with unusual symptom patterns that don't perfectly match any single disorder. Let's break down the major categories and their characteristic features.

Patients with beta-thalassemia fundamentally struggle with insufficient red blood cell production. This shortage manifests as classic anemia symptoms: unusual pallor, persistent fatigue, breathlessness with minimal exertion, and delayed growth in children. Every tissue throughout the body receives less oxygen than it needs.

The body tries to compensate by ramping up red blood cell production. But here's the cruel irony—these newly made cells either die prematurely or never fully mature. This creates a vicious cycle where patients must also break down more old cells than normal. The breakdown process places stress on the liver and spleen, which handle red blood cell recycling. Patients often develop jaundice that telltale yellowing of skin and eyes along with hepatosplenomegaly (enlargement of both organs).

Severe beta-thalassemia introduces another danger: iron overload toxicity. The body, desperate to build more red blood cells, absorbs excessive iron from food. Patients requiring regular blood transfusions and many do need them to survive accumulate even more iron, which can damage the heart, liver, and endocrine system over time.

The hallmark of sickle cell disease is unmistakable: red blood cells lose their flexible disc shape and become rigid, sticky crescents. These sickled erythrocytes can't squeeze through tiny blood vessels. Instead, they get stuck, blocking blood flow and starving oxygen-sensitive tissues downstream.

The consequences are far-reaching. Patients experience acute pain crises when blockages occu episodes that can be severe enough to require hospitalization. They face increased infection risk, progressive organ damage, and even stroke when blood vessels in the brain become occluded. The most vulnerable tissues include joints, lung tissue, kidney parenchyma, splenic tissue, and brain matter.

Many sickle cell patients also deal with anemia. Their red blood cells constantly shift shape round in well-oxygenated environments, sickled when oxygen runs low. This constant morphological stress dramatically shortens cell lifespan. Normal red cells last months; sickle cells survive only one to three weeks. Some patients require frequent transfusions, which like thalassemia patients puts them at risk for secondary iron overload.

Oxygen transport disorders represent a distinct category with unique clinical features. Unlike thalassemia (too few cells) or sickle cell (misshapen cells), Oxygen transport disorders present differently. Patients typically produce adequate numbers of red blood cells, though some experience mild anemia. The core problem lies in oxygen delivery efficiency the blood simply doesn't unload oxygen to tissues properly.

The physical signs can be striking. Patients may develop cyanosis: a bluish discoloration of the skin most noticeable in the lips and fingertips. They experience dyspnea (shortness of breath) with activity. Perhaps most dramatically, their blood itself may appear purple or brownish rather than the healthy bright red of well-oxygenated blood a visual reminder that something has gone wrong at the molecular level.

What makes these conditions particularly tricky? Standard pulse oximetry can be misleading. Some abnormal hemoglobins interfere with the device's light absorption, producing falsely reassuring readings. Arterial blood gas measurements with co oximetry provide more accurate assessment.

Treatment varies by the specific hemoglobin variant involved. Some patients need no intervention, while others benefit from avoiding certain medications or situations that worsen oxygen affinity. Severe cases may require exchange transfusion to replace abnormal hemoglobin with normal donor hemoglobin.

A Legacy of Molecular Understanding

Hemoglobin disorders hold an important place in medical history they were among the first diseases understood at the molecular genetic level. Groundbreaking discoveries starting in the late 1940s transformed these once uniformly fatal conditions into manageable chronic illnesses. Today, patients can combine medical interventions with lifestyle modifications to maintain good health. Unfortunately, this progress hasn't reached everyone millions of children worldwide still die from these disorders annually, highlighting巨大的 healthcare disparities in different regions.

Considerations for Carriers

Allele carriers people who inherit one affected gene copy sometimes experience mild symptoms. They may develop subtle anemia, and individuals with one sickle cell allele might notice some sickling during extreme conditions: very high altitudes, significant dehydration, or extraordinarily strenuous activities. These individuals should also follow the lifestyle guidance below, though their precautions can be less stringent than for those with full-blown disease.

Lifestyle Modifications for Better Outcomes

Medical Interventions: Standard Approaches

|

Fruits |

Home-Made Foods |

|

Apples - low iron, good for overload risk |

Lentil soup - iron-rich, excellent for anemic patients |

|

Pomegranates - natural iron source |

Spinach curry - boosts red blood cell production |

|

Citrus fruits - vitamin C aids iron absorption |

Fortified rice - supports erythropoiesis |

|

Bananas - easy to digest, energy-rich |

Bone broth - mineral-dense, easily absorbed |

|

Watermelon - hydrating, kidney-friendly |

Beetroot salads - natural hemoglobin booster |

|

Dried figs - concentrated iron source |

Dal khichdi - balanced, gentle on digestion |

|

Berries - antioxidants reduce oxidative stress |

Green smoothies - nutrient-packed options |

|

Avocado - healthy fats, vitamin E |

Steamed vegetables - preserves nutrient content |

|

Papaya - digestive support, vitamins |

Homemade juices - controlled ingredients |

|

Dates - quick energy, iron-rich |

Whole grain roti - fiber and B vitamins |

Hemoglobin disorders represent a diverse group of inherited conditions that impact patient health across the lifespan from silent carrier states to life-threatening disease manifestations. Understanding the underlying genetic mechanisms, recognizing variable clinical presentations, and implementing evidence-based management strategies allows clinicians to significantly improve patient outcomes.

The therapeutic landscape continues evolving rapidly. While traditional approaches like transfusion support, iron chelation, and hydroxyurea remain cornerstones of care, curative options including hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and emerging gene therapies offer hope for permanent solutions. The key lies in early diagnosis, patient education, and personalized treatment plans that address each individual's unique genetic and clinical profile.

As research advances our understanding of fetal hemoglobin reactivation and molecular correction techniques, the future promises even better outcomes for patients worldwide. Until then, thoughtful combination of medical interventions and lifestyle modifications remains essential for optimizing quality of life.